Forever Free Art by Afrian American Women Artists and Exhibit and Conference

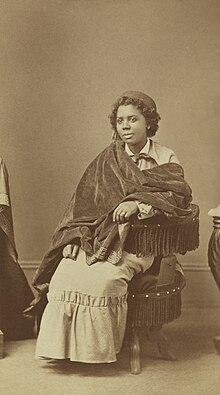

| Edmonia Lewis | |

|---|---|

| "Wildfire" | |

| |

| Born | Mary Edmonia Lewis July 4, 1844 Town of Greenbush, Rensselaer Canton, New York, U.s.a. |

| Died | September 17, 1907(1907-09-17) (anile 63) London, United kingdom |

| Nationality | American, Mississauga |

| Education | New-York Central College, Oberlin |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Movement | Late Neoclassicism |

| Patron(due south) | Numerous patrons, American and European |

Mary Edmonia Lewis, "Wildfire" (c. July 4, 1844 – September 17, 1907), was an American sculptor, of mixed African-American and Native American (Mississauga Ojibwe) heritage. Born free in Upstate New York, she worked for virtually of her career in Rome, Italy. She was the first African-American and Native American sculptor to achieve national then international prominence.[1] She began to gain prominence in the United States during the Civil State of war; at the end of the 19th century, she remained the merely Black adult female artist who had participated in and been recognized to any extent by the American creative mainstream.[2] In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Edmonia Lewis on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[iii]

Her piece of work is known for incorporating themes relating to Black people and indigenous peoples of the Americas into Neoclassical-style sculpture.

Biography [edit]

Early on life [edit]

Co-ordinate to the American National Biography, reliable data nearly her early life is limited, and Lewis "was ofttimes inconsistent in interviews even with basic facts virtually her origins, preferring to present herself as the exotic product of a childhood spent roaming the forests with her mother's people."[4] On official documents she gave 1842, 1844, and 1854 equally her birth year.[5]

She was born near Albany, New York.[four] Nearly of her girlhood was apparently spent in Newark, New Jersey.[half-dozen] [7]

Her mother, Catherine Mike Lewis, was African-Native American, of Mississauga Ojibwe and African-American descent.[viii] [9] She was an excellent weaver and craftswoman. Ii different African-American men are mentioned in different sources as being her father. The first is Samuel Lewis,[4] who was Afro-Haitian and worked as a valet (admirer's servant).[10] [11] Other sources say her father was the writer on African Americans, Robert Benjamin Lewis.[12] Her half-blood brother Samuel, who is treated at some length in a history of Montana,[13] said that their male parent was "a West Indian Frenchman", and his female parent "part African and partly a descendant of the educated Narragansett Indians of New York state."[14] (the Narragansett people are originally from Rhode Isle.)

By the time Lewis reached the age of nine, both of her parents had died; Samuel Lewis died in 1847[15] and Robert Benjamin Lewis in 1853. Her 2 maternal aunts adopted her and her older one-half-brother Samuel.[8] Samuel was born in 1835 to his father of the same proper name, and his showtime married woman, in Republic of haiti. The family came to the Us when Samuel was a young child.[15] Samuel became a barber at age 12 after their father died.[15]

The children lived with their aunts most Niagara Falls, New York, for about four years. Lewis and her aunts sold Ojibwe baskets and other items, such as moccasins and embroidered blouses, to tourists visiting Niagara Falls, Toronto, and Buffalo. During this time, Lewis went past her Native American name, Wildfire, while her brother was called Sunshine. In 1852, Samuel left for San Francisco, California, leaving Lewis in the care of a Captain S. R. Mills.

By the fourth dimension she got to college, Lewis was economically privileged, because her older brother Samuel had made a fortune in the California gold rush and "supplied her every want anticipating her wishes subsequently the style and style of a person of aplenty income".[14]

In 1856, Lewis enrolled in a pre-higher program at New York Primal College, a Baptist abolitionist schoolhouse.[eight] At McGrawville, Lewis met many of the leading activists who would become mentors, patrons, and possible subjects for her work as her artistic career adult.[16] In a afterward interview, Lewis said that she left the schoolhouse after three years, having been "declared to exist wild."[17]

Until I was twelve years former I led this wandering life, angling and swimming...and making moccasins. I was then sent to schoolhouse for three years in [McGrawville], but was alleged to be wild—they could practise nix with me.

—Edmonia Lewis[18]

However, her academic tape at Central College (1856–fall 1858) has been located, and her grades, "carry", and omnipresence were all exemplary. Her classes included Latin, French, "grammar", arithmetic, cartoon, composition, and declamation (public speaking).[19]

Education [edit]

In 1859, when Edmonia Lewis was about 15 years sometime, her brother Samuel and abolitionists sent her to Oberlin, Ohio, where she attended the secondary Oberlin Academy Preparatory School for the full, three-year grade,[xx] before entering Oberlin Collegiate Institute (since 1866, Oberlin College),[21] 1 of the first U.S. college-learning institutions to acknowledge women and people of differing ethnicities.[22] The Ladies' Department was designed "to give Young Ladies facilities for the thorough mental subject, and the special training which will authorize them for didactics and other duties of their sphere."[23] She changed her name to Mary Edmonia Lewis[24] and began to study art.[25] Lewis boarded with Reverend John Go along and his married woman from 1859 until she was forced from the higher in 1863. At Oberlin, with a student population of one yard, Lewis was one of only thirty students of color.[26] Reverend Keep was white, a member of the lath of trustees, an avid abolitionist, and a spokesperson for coeducation.[17]

Mary said later that she was subject to daily racism and bigotry. She, and other female students, were rarely given the opportunity to participate in the classroom or speak at public meetings.[27]

During the winter of 1862, several months after the start of the Civil War, an incident occurred between Lewis and two Oberlin classmates, Maria Miles and Christina Ennes. The iii women, all boarding in Keep's dwelling, planned to go sleigh riding with some young men later that 24-hour interval. Before the sleighing, Lewis served her friends a beverage of spiced wine. Shortly subsequently, Miles and Ennes fell severely ill. Doctors examined them and concluded that the two women had some sort of poisonous substance in their system, supposedly cantharides, a reputed aphrodisiac. For a fourth dimension it was not sure that they would survive. Days later, it became apparent that the two women would recover from the incident. Regime initially took no action.

News of the controversial incident rapidly spread throughout Ohio. In the town of Oberlin, where the general population was not equally progressive as at the higher, while Lewis was walking home alone one night she was dragged into an open field past unknown assailants, desperately beaten, and left for dead.[28] After the attack, local authorities arrested Lewis, charging her with poisoning her friends. John Mercer Langston, an Oberlin College alumnus and the showtime African-American lawyer in Ohio, represented Lewis during her trial. Although nearly witnesses spoke confronting her and she did not evidence, Chapman moved successfully to have the charges dismissed: the contents of the victims' stomachs had non been analyzed and in that location was, therefore, no evidence of poisoning, no corpus delicti.[29] [30] [6]

The residual of Lewis' time at Oberlin was marked by isolation and prejudice. Nigh a twelvemonth after the poisoning trial, Lewis was accused of stealing artists' materials from the college. She was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Simply a few months afterwards she was charged with aiding and abetting a burglary. At this point she had had enough, and left.[6] Another written report says that she was forbidden from registering for her last term, leaving her unable to graduate.[31]

Fine art career [edit]

Boston [edit]

After college, Lewis moved to Boston in early on 1864, where she began to pursue her career as a sculptor. She repeatedly told a story about encountering in Boston a statue of Benjamin Franklin, non knowing what it was or what to call it, but concluding she could make a "stone man" herself.[32]

The Keeps wrote a letter of introduction on Lewis' behalf to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in Boston, every bit did Henry Highland Garnet.[33] He introduced her to already established sculptors in the area, as well as writers who publicized Lewis in the abolitionist printing.[34] Finding an instructor, nevertheless, was not easy for her. Three male sculptors refused to instruct her earlier she was introduced to the moderately successful sculptor, Edward Augustus Brackett (1818–1908), who specialized in marble portrait busts.[35] [36] [37] His clients were some of the almost important abolitionists of the day, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Wm. Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, and John Brown.[36]

To instruct her, he lent her fragments of sculptures to re-create in clay, which he critiqued.[37] Nether his tutelage, she crafted her own sculpting tools and sold her showtime slice, a sculpture of a woman's hand, for $8.[38] Anne Whitney, a fellow sculptor and friend of Lewis', wrote in an 1864 letter to her sister that Lewis's relationship with her instructor did not terminate amicably, but did not disembalm the reason for the split up.[36] Lewis opened her studio to the public in her first solo exhibition in 1864.[39]

Lewis was inspired by the lives of abolitionists and Civil State of war heroes. Her subjects in 1863 and 1864 included some of the most famous abolitionists of her mean solar day: John Brown and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.[forty] When she met Union Colonel Shaw, the commander of an African-American Civil War regiment from Massachusetts, she was inspired to create a bosom of his likeness, which impressed the Shaw family, who purchased it.[41] Lewis then fabricated plaster-bandage reproductions of the bust; she sold one hundred at 15 dollars apiece.[42] This was her most famous work to date and the money she earned from the busts immune her to eventually move to Rome.[43] [44] Anna Quincy Waterston, a poet, then wrote a verse form about both Lewis and Shaw.[45]

From 1864 to 1871, Lewis was written about or interviewed past Lydia Maria Child, Elizabeth Peabody, Anna Quincy Waterston, and Laura Curtis Bullard: all important women in Boston and New York abolitionist circles.[36] Considering of these women, manufactures about Lewis appeared in important abolitionist journals, including Broken Fetter, the Christian Register, and the Contained, every bit well every bit many others.[40] Lewis was aware of her reception in Boston. She was not opposed to the coverage she received in the abolitionist press, and she was non known to turn down monetary aid, only she could not tolerate the false praise. She knew that some did not really capeesh her art, just saw her as an opportunity to limited and bear witness their support for homo rights.[46]

Early works that proved highly popular included medallion portraits of the abolitionists John Brown, described as "her hero",[33] and Wm. Lloyd Garrison. Lewis also drew inspiration from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his piece of work, particularly his epic poem The Song of Hiawatha. She fabricated several busts of its leading characters, which he drew from Ojibwe legend.[47]

Rome [edit]

While in Rome, Lewis adopted the neoclassical style of sculpture, every bit seen in Bosom of Dr. Dio Lewis (1868).[48]

I was practically driven to Rome in order to obtain the opportunities for art culture, and to find a social atmosphere where I was not constantly reminded of my color. The land of liberty had no room for a colored sculptor.[33]

The success and popularity of these works in Boston allowed Lewis to bear the cost of a trip to Rome in 1866.[49] On her 1865 passport is written, "M. Edmonia Lewis is a Black girl sent by subscription to Italy having displayed great talents as a sculptor".[l] The established sculptor Hiram Powers gave her infinite to work in his studio.[51] She entered a circle of expatriate artists and established her ain space inside the former studio of 18th-century Italian sculptor Antonio Canova,[52] just off the Piazza Barberini.[44] She received professional back up from both Charlotte Cushman, a Boston actress and a pivotal effigy for expatriate sculptors in Rome, and Maria Weston Chapman, a dedicated worker for the anti-slavery crusade.[53]

Lewis spent most of her adult career in Rome, where Italy's less pronounced racism immune increased opportunity to a black creative person.[2] There Lewis enjoyed more social, spiritual, and artistic freedom than what she had had in the United States. Being a Catholic, her experience in Rome as well immune her both spiritual and physical closeness to her faith. In America, Lewis would have had to go on relying on abolitionist patronage; but Italy allowed her to make her own in the international fine art globe.[54] She began sculpting in marble, working within the neoclassical style, simply focusing on naturalism inside themes and images relating to black and American Indian people.[55] The surroundings of the classical earth greatly inspired her and influenced her piece of work, in which she recreated the classical art fashion—such as presenting people in her sculptures every bit draped in robes rather than in contemporary clothing.[56]

She wears a red cap in her studio, which is very picturesque and effective; her face is a bright, intelligent, and expressive i. Her manners are kid-like, simple and most winning and pleasing.... There is something in human nature...which makes everyone admire a dauntless and heroic spirit; and if people are not always set up to lend a helping hand to struggling genius, they are all eager to applaud when those struggles are drowned with success. The hour of applause has come to Edmonia Lewis.[57]

Lewis was unique in the mode she approached sculpting abroad. She insisted on enlarging her clay and wax models in marble herself, rather than hire native Italian sculptors to do information technology for her – the common practice at the fourth dimension. Male sculptors were largely skeptical of the talent of female sculptors, and often accused them of not doing their own work.[54] Harriet Hosmer, a swain sculptor and expatriate, also did this. Lewis also was known to brand sculptures before receiving commissions for them, or sent unsolicited works to Boston patrons requesting that they raise funds for materials and shipping.[55]

While in Rome, Lewis connected to express her African-American and Native American heritage. One of her more famous works, "Forever Free", depicted a powerful image of an African-American man and women emerging from the bonds of slavery. Another sculpture Lewis created was called "The Arrow Maker", which showed a Native American father teaching his daughter how to make an arrow.[43]

Her work sold for large sums of money. In 1873 an article in the New Orleans Picayune stated: "Edmonia Lewis had snared two 50,000-dollar commissions." Her new-establish popularity fabricated her studio a tourist destination.[58] Lewis had many major exhibitions during her rise to fame, including one in Chicago, Illinois, in 1870, and in Rome in 1871.[25]

The Expiry of Cleopatra [edit]

A major coup in her career was participating in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.[59] For this, she created a monumental three,015-pound marble sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra, portraying the queen in the throes of decease.[60] This piece depicts the moment popularized by Shakespeare in Antony and Cleopatra, in which Cleopatra had allowed herself to be bitten past a poisonous asp post-obit the loss of her crown.[26] Of the slice, J. South. Ingraham wrote that Cleopatra was "the nigh remarkable piece of sculpture in the American section" of the Exposition.[61] Much of the viewing public was shocked past Lewis's frank portrayal of death, only the statue drew thousands of viewers yet.[62] Cleopatra was considered a woman of both sensuous beauty and demonic power, and[63] her self-anything has been portrayed numerously in art, literature and picture palace. In Death of Cleopatra, Edmonia Lewis added an innovative flair by portraying the Egyptian queen in a disheveled, inelegant manner, a departure from the refined, composed Victorian approach of representing death.[64] Considering Lewis'south interest in emancipation imagery as seen in her work Forever Free, it is not surprising that Lewis eliminated Cleopatra's usual companion figures of loyal slaves from her work. Lewis's The Expiry of Cleopatra may have been a response to the civilisation of the Centennial Exposition, which historic one hundred years of the Usa being congenital around the principles of liberty and liberty, a celebration of unity despite centuries of slavery, the recent Civil State of war, and the failing attempts and efforts of Reconstruction. In order to avoid whatever acknowledgement of black empowerment by the Centennial, Lewis's sculpture could non take direct addressed the field of study of Emancipation.[26] Although her white contemporaries were also sculpting Cleopatra and other comparable subject affair (such every bit Harriet Hosmer's Zenobia), Lewis was more than prone to scrutiny on the premise of race and gender due to the fact that she, similar Cleopatra, was female:

The associations between Cleopatra and a blackness Africa were so profound that...any depiction of the aboriginal Egyptian queen had to argue with the issue of her race and the potential expectation of her blackness. Lewis' white queen gained the aura of historical accuracy through primary enquiry without sacrificing its symbolic links to abolitionism, blackness Africa, or black diaspora. But what it refused to facilitate was the racial objectification of the artist'south trunk. Lewis could not and so readily get the subject of her own representation if her subject was corporeally white.[65]

Subsequently being placed in storage, the statue was moved to the 1878 Chicago Interstate Exposition, where information technology remained unsold. So the sculpture was acquired by a gambler past the name of "Blind John" Condon, who purchased information technology from a saloon on Clark Street to mark the grave of a Racehorse named "Cleopatra".[66] The grave was in front end of the grandstand of his Harlem race rail in the Chicago suburb of Forest Park, where the sculpture remained for nearly a century until the country was bought by the U.S. Mail service[67] and the sculpture was moved to a structure storage yard in Cicero, Illinois.[68] [67] While at the storage yard, The Decease of Cleopatra sustained extensive harm at the hands of well-pregnant Boy Scouts who painted and caused other damage to the sculpture. Dr. James Orland, a dentist in Forest Park and member of the Forest Park Historical Social club, acquired the sculpture and held it in private storage at the Forest Park Mall.

Afterwards, Marilyn Richardson, an assistant professor in the erstwhile The Writing Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Engineering science (MIT), and after curator and scholar of African-American art, went searching for The Expiry of Cleopatra for her biography of Lewis. Richardson was directed to the Forest Park Historical Society and Dr. Orland by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who had earlier been contacted by the historical society regarding the sculpture. Richardson, after confirming the sculpture's location, contacted African-American bibliographer Dorothy Porter Wesley, and the two gained the attention of NMAA's George Gurney.[69] According to Gurney, Curator Emeritus at the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[70] the sculpture was in a race track in Forest Park, Illinois, during World State of war II. Finally, the sculpture came under the purview of the Forest Park Historical Society, who donated it to Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1994.[68] Chicago-based Andrezej Dajnowski, in conjunction with the Smithsonian, spent $30,000 to restore information technology to its near-original state. The repairs were all-encompassing, including the nose, sandals, hands, mentum, and extensive "sugaring" (disintegration.) [69]

Later on career [edit]

A testament to Lewis'south renown as an artist came in 1877, when sometime U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant commissioned her to do his portrait. He sabbatum for her equally a model and was pleased with her finished piece.[71] She also contributed a bust of Massachusetts abolitionist senator Charles Sumner to the 1895 Atlanta Exposition.[72]

In the belatedly 1880s, neoclassicism declined in popularity, equally did the popularity of Lewis's artwork. She continued sculpting in marble, increasingly creating altarpieces and other works for Catholic patrons. A bust of Christ, created in her Rome studio in 1870, was rediscovered in Scotland in 2015.[44] In the art world, she became eclipsed past history, and lost fame. By 1901 she had moved to London.[73] [a]

The events of her afterwards years are non known.[25]

Death [edit]

From 1896 to 1901 Lewis lived in Paris.[44] She so relocated to the Hammersmith area of London, England, before her death on September 17, 1907, in the Hammersmith Borough Hospital.[74] Co-ordinate to her death certificate, the cause of her death was chronic kidney failure (Bright's disease).[27] She is buried in St. Mary's Cosmic Cemetery, in London.[75]

There were earlier theories that Lewis died in Rome in 1907 or, alternatively, that she had died in Marin County, California, and was cached in an unmarked grave in San Francisco.[76]

Edmonia Lewis' grave subsequently restoration

In 2017, a GoFundMe by E Greenbush, New York, boondocks historian Bobbie Reno was successful, and Edmonia Lewis's grave was restored.[77] The piece of work was done by the E One thousand Lander Co. in London.

Reception [edit]

As a black artist, Edmonia Lewis had to be conscious of her stylistic choices, as her largely white audition often gravely misread her work as self-portraiture. In order to avert this, her female figures typically possess European features.[2] Lewis had to residuum her own personal identity with her artistic, social, and national identity, a tiring action that affected her art.[78]

In her 2007 work, Charmaine Nelson wrote of Lewis:

It is hard to overstate the visual incongruity of the black-Native female body, let alone that identity in a sculptor, within the Roman colony. As the first black-Native sculptor of either sexual activity to achieve international recognition inside a western sculptural tradition, Lewis was a symbolic and social anomaly within a dominantly white bourgeois and aristocratic community.[2]

Personal life [edit]

Lewis never married and had no known children.[79] According to her biographer, Dr. Marilyn Richardson, there is no definite information about her romantic involvement with anyone.[lxxx] Nevertheless, in 1873 her engagement was appear,[81] and in 1875, still engaged, his skin color was revealed to be the aforementioned as hers, although his name is non given.[82] There is no farther reference to this appointment.

Her half-brother Samuel became a barber in San Francisco, eventually moving to mining camps in Idaho and Montana. In 1868, he settled in the city of Bozeman, Montana, where he fix upward a barber shop on Main Street. He prospered, somewhen investing in commercial existent estate, and subsequently built his own home which nonetheless stands at 308 Southward Bozeman Avenue. In 1999 the Samuel Lewis Firm was placed on the National Register of Celebrated Places. In 1884, he married Mrs. Melissa Railey Bruce, a widow with six children. The couple had 1 son, Samuel E. Lewis (1886–1914), who married merely died childless. The elder Lewis died subsequently "a curt illness" in 1896 and is buried in Sunset Hills Cemetery in Bozeman.[15] The mayor of Bozeman was a pallbearer.[xv]

Popular works [edit]

Old Arrow-Maker and his Daughter (1866) [edit]

This sculpture was inspired past Lewis'south Native American heritage. An pointer-maker and his girl sit on a round base, dressed in traditional Native American clothes. The male person effigy has recognizable Native American facial features, but non the daughter. As white audiences' misread her work as cocky-portraiture, she often removed all facial features associated with "colored" races in female portrayal.[83]

Forever Free (1867) [edit]

The words "forever gratis" are taken from President Lincoln'south Emancipation Proclamation.

This white marble sculpture represents a man standing, staring up, and raising his left arm into the air. Wrapped around his left wrist is a chain; however, this chain is not restraining him. To his correct is a adult female kneeling with her hands held in a prayer position. The man's correct hand is gently placed on her correct shoulder. Forever Complimentary is a celebration of black liberation, salvation, and redemption, and represents the emancipation of African-American slaves. Lewis attempted to break stereotypes of African-American women with this sculpture. For example, she portrayed the woman equally completely dressed while the homo was partially dressed. This drew attention away from the notion of African-American women being sexual figures. This sculpture also symbolizes the end of the Civil War. While African Americans were legally free, they continued to be restrained, shown by the fact that the couple had chains wrapped effectually their bodies. The representation of race and gender has been critiqued by modernistic scholars, specially the Eurocentric features of the female person figure. This slice is held by Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[84]

Hagar (1868) [edit]

Lewis had a tendency to sculpt historically strong women, as demonstrated not merely in Hagar simply also in Lewis'due south Cleopatra piece. Lewis as well depicted ordinary women in extreme situations, emphasizing their strength.[79] Hagar is inspired by a character from the Old Testament, the handmaid or slave of Abraham's wife Sarah. Beingness unable to conceive a kid, Sarah gave Hagar to Abraham, in order to bear him a son. Hagar gave nascence to Abraham's firstborn son Ishmael, and after Sarah gave birth to her own son Isaac, she resented Hagar and fabricated Abraham "bandage her into the wilderness". The slice was made of white marble, and Hagar is standing as if about to walk on, with her hands clasped in prayer and staring slightly up merely non direct across. Lewis uses Hagar to symbolize the African mother in the U.s., and the frequent sexual abuse of African women by white men.

The Death of Cleopatra (1876) [edit]

Discussed above.

In popular media [edit]

- Namesake of the Edmonia Lewis Center for Women and Transgender People at Oberlin College.[85]

- Written about in Olio, which is a book of poetry written by Tyehimba Jess that was released in 2016.[86] [87] That book won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.[88]

- Honored with a Google Doodle on February 1, 2017.[89]

- Stone Mirrors: The Sculpture and Silence of Edmonia Lewis, by Jeannine Atkins (2017) is a juvenile biographical novel in verse.[90]

- A belated obituary was published in The New York Times in 2018 as role of their Overlooked series.[91]

- The acknowledged novel, La linea del colori: Il One thousand Tour di Lafanu Dark-brown, by Somalian Igiaba Scelgo (Florence: Giunti, 2020), in Italian, combines the characters of Edmonia Lewis and Sarah Parker Remond and is dedicated to Rome and to these ii figures.

- She features as a "Dandy Artist" in the video game Civilization Six.

- Lewis is the subject of a stage play entitled "Edmonia" by Barry M. Putt, Jr., presented by Beacon Theatre Productions in Philadelphia, PA in 2021. "Edmonia" stage play.

- Lewis had a U.S. postal stamp unveiled in her accolade on January 26, 2022.[92] [93]

List of major works [edit]

- John Brown medallions, 1864–65

- Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (plaster), 1864

- Anne Quincy Waterston, 1866

- A Freed Woman and Her Child, 1866

- The Old Arrow-Maker and His Girl, 1866

- The Marriage of Hiawatha, 1866–67[94]

- Forever Free, 1867

- Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (marble), 1867–68

- Hagar in the Wilderness, 1868

- Madonna Holding the Christ Child, 1869[94]

- Hiawatha, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1868[b]

- Minnehaha, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1868[b]

- Indian Gainsay, Carrara marble, xxx" loftier, collection of the Cleveland Museum of Fine art, 1868[95]

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1869–71

- Bust of Abraham Lincoln, 1870[c]

- Asleep, 1872[c]

- Awake, 1872[c]

- Poor Cupid, 1873

- Moses, 1873

- Bust of James Peck Thomas, 1874, collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, her simply known portrait of a freed slave[97]

- Hygieia, 1874

- Hagar, 1875

- The Expiry of Cleopatra, marble, 1876, collection of Smithsonian American Art Museum

- John Chocolate-brown, 1876, Rome, plaster bust

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1876, Rome, plaster bust

- General Ulysses Due south. Grant, 1877–78

- Veiled Bride of Jump, 1878

- John Brown, 1878–79

- The Admiration of the Magi, 1883[98]

- Charles Sumner, 1895

Gallery [edit]

-

Edmonia Lewis, Anna Quincy Waterston, 1866, photo by David Finn, ©David Finn Annal, Department of Paradigm Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

-

Edmonia Lewis, Poor Cupid, 1872–1876, photo by David Finn, ©David Finn Archive, Section of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

-

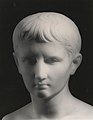

Edmonia Lewis, Young Octavian, 1873, photo by David Finn, ©David Finn Annal, Department of Epitome Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

-

Edmonia Lewis, Hagar, 1875, photograph past David Finn, ©David Finn Annal, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Fine art Library, Washington, DC

-

Edmonia Lewis, Former Arrow Maker, 1866–1872, photograph by David Finn, ©David Finn Archive, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

Posthumous exhibitions [edit]

- Art of the American Negro Exhibition, American Negro Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1940.[99] [100]

- Howard Academy, Washington, D.C., 1967.

- Vassar Higher, New York, 1972.

- Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 2008.

- Edmonia Lewis and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Images and Identities at the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 18 February–iii May 1995.

- Smithsonian American Fine art Museum, Washington, D.C., June 7, 1996 – April fourteen, 1997.

- Wildfire Test Pit, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin Higher, Oberlin, Ohio, Baronial 30, 2016 – June 12, 2017.[101]

- Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, (2019), Minneapolis Plant of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States.[102]

- Edmonia Lewis' Bust of Christ, Mountain Stuart, United kingdom[103]

Encounter too [edit]

- List of female sculptors

- Samuel Lewis House (Bozeman, Montana): Brother'southward house in Montana

- Moses Jacob Ezekiel, another American sculptor in Rome around the same time flow, and also included in 1876 Philadelphia exposition.

- Women in the fine art history field

Notes [edit]

- ^ The 1901 British census lists her equally lodging at 37 Store Street, Holborn, supported by "own ways". She gives her age every bit 59, her occupation as "Artist (modeller)", and her birthplace as "India".

- ^ a b The Newark Museum lists the date of the sculpture every bit 1868; nonetheless, Wolfe 1998, p. 120 gives the dates 1869–71.

- ^ a b c The original sculpture is housed in the California Room of San José Public Library. The statues Awake (1872), Asleep (1872), and Bosom of Abraham Lincoln (1870) were purchased in 1873 by the San Jose Library Association (forerunner to the San Jose Public Library) and transferred to the San Jose Public Library.[96]

References [edit]

- ^ "Lewis, (Mary) Edmonia". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. 2003. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T050781. ISBN978-1-884446-05-4 . Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Nelson 2007

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books II. ISBN1-57392-963-8.

- ^ a b c Richardson, Marilyn (2000). "Lewis, Edmonia (1840–subsequently 1909), sculptor". American National Biography . Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Richardson, Marilyn (2008). "Edmonia Lewis and the Boston of Italy". 5 International Conference on the Metropolis and the Book. OCLC 499231062. Archived from the original on March four, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cleveland-Peck, Patricia (Oct 2007). "Casting the outset stone". History Today. Vol. 57, no. ten – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Cleveland-Peck, Patricia (Oct 2007). "Casting the first rock". History Today. Vol. 57, no. 10 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ a b c Buick 2010, p. 4

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 12

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 15

- ^ Hartigan 1985

- ^ "The great sculptress, Edmonia Lewis". Los Angeles Daily Herald. October 14, 1873. p. 4 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ Miller, Joaquin (1894). An illustrated history of the state of Montana. Chicago: Lewis Publishing. pp. 374–376.

- ^ a b "Samuel Lewis dead". Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana). April 1, 1896. p. nine.

- ^ a b c d e Pickett 2002

- ^ Richardson 2008a

- ^ a b Buick 2010, p. v

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 111

- ^ Henderson, Albert (2013). "'I was declared to exist wild.' Mary E. Lewis'southward grades at New York Cardinal College, McGrawville, NY". BLOG - Searching for Edmonia Lewis. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Blodgett, Geoffrey. "John Mercer Langston and the Instance of Edmonia Lewis: Oberlin, 1862." The Periodical of Negro History, vol. 53, no. 3, 1968, pp. 201–218. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2716216.

- ^ Phaidon Editors (2019). Not bad women artists. Phaidon Press. p. 243. ISBN978-0714878775.

- ^ "Oberlin History". Oberlin College & Conservatory. Archived from the original on sixteen September 2019. Retrieved ii February 2017.

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 7

- ^ Hartigan 1985; Buick 2010, p. 5

- ^ a b c Plowden 1994

- ^ a b c Gold 2012

- ^ a b Henderson 2012 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHenderson2012 (assistance)

- ^ Katz 1993 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKatz1993 (help); Woods 1993

- ^ Katz 1993 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKatz1993 (assist)

- ^ Smith, Jr., J. Dirt (1993). Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 409. ISBN0812231813.

- ^ Buick 2010, p. ten

- ^ "Edmonia Lewis, the American sculptress". People's Advocate (Osage Mission, Kansas). 22 June 1871. p. 1 – via newspapers.com. \

- ^ a b c "Seeking equality abroad". The New York Times. December 29, 1878. p. 5. ProQuest 93646081.

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 11

- ^ "Edward Augustus Brackett". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on two August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Buick 2010, p. 12

- ^ a b Chadwick 2012, p. 223

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 43

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 44

- ^ a b Buick 2010, p. 13

- ^ Wolfe 1998, pp. 46–49

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 14

- ^ a b "Edmonia Lewis". Biography.com (published 2 Apr 2014). 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on ii August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Moorhead, Joanna (10 October 2021). "Feted, forgotten, redeemed: how Edmonia Lewis fabricated her marking". The Guardian.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 49

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 16

- ^ Gold 2012, p. 325

- ^ "Bust of Dr Dio Lewis" (museum catalog record). The Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ Chadwick 2012

- ^ "Passport application 21933". Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 53

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 55

- ^ Chadwick 2012, p. 225

- ^ a b Buick 2010

- ^ a b Chadwick 2012, p. 30

- ^ Lewis, Samella (2003). "The Diverse Quests for Professional person Statues". African American Art and Artists. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN978-0520239357. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Edmonia Lewis". Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin). 12 May 1871. p. ane – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Tufts, Eleanor (1974). "The Nineteenth Century". Our Hidden Heritage: five centuries of women artists. New York: Paddington Press. ISBN978-0448230351 . Retrieved 1 Feb 2017.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 93

- ^ Wolfe 1998, pp. 97, 102

- ^ Wolfe 1998, pp. 97–99

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 100

- ^ Patton, Sharon F. (1998). African-American Art . New York: Oxford Academy Press. p. 97. ISBN9780192842138.

- ^ Nelson 2007, p. 168

- ^ Nelson 2007, p. 178

- ^ "Edmonia Lewis". Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia of Earth Biography. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved vii March 2015.

- ^ a b New York Amsterdam News 1996

- ^ a b Smithsonian 2018

- ^ a b May 1996, p. 20

- ^ Kaplan, Howard (29 September 2011). "Sculpting a Career with Curator George Gurney". Eye Level (blog post). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved i August 2018.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, pp. 108–109

- ^ Perdue, Theda (2010). Race and the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition of 1895. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. twoscore. ISBN978-0820340357.

- ^ "Demography records". nationalarchives.gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. The National Archives. Archived from the original on xi July 2018. Retrieved i Baronial 2018.

- ^ Richardson, Marilyn (nine January 2011). "Sculptor's Decease Appointment Unearthed: Edmonia Lewis Died in London in 1907". Art Set up Daily. Archived from the original on iv February 2017. Retrieved 1 Feb 2017.

- ^ Lavin, Talia (2 November 2015). "The Life and Death of Edmonia Lewis, Spinster and Sculptor". The Toast. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved xviii March 2016.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 110

- ^ Talia, Lavin (2018). "The Decades-Long Quest to Find and Honor Edmonia Lewis's Grave". Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-27 .

- ^ Kleeblatt, Norman L (1998). "Main Narratives/Minority Artists". Fine art Periodical. 57 (three): 29–35. doi:10.1080/00043249.1998.10791890.

- ^ a b Perry 1992

- ^ Tyrkus, Michael J.; Bronski, Michael, eds. (1997). "Edmonia Lewis". Gay & Lesbian Biography. Gale In Context: Biography. St. James Press. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ "Personals". The Boston Globe. 27 March 1873. p. 5 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "For and about the ladies". Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota). 29 July 1875. p. 2.

- ^ Buick 2010, p. 66

- ^ Collins, Lisa G. (2002). "Female person Body in Art". The Art of History: African American Women Artists Appoint the Past. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN978-0813530222 . Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Edmonia Lewis Middle for Women and Transgender People". Oberlin College & Conservatory. 24 Oct 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 1 Baronial 2018.

- ^ Grumbling, Megan (20 January 2018). "Olio". The Cafe Review. Archived from the original on 16 Baronial 2018. Retrieved sixteen August 2018.

- ^ "Fiction Book Review: Olio by Tyehimba Jess". PublishersWeekly.com. Archived from the original on nineteen February 2017. Retrieved eighteen February 2017.

- ^ "2017 Pulitzer Prize Winners and Nominees". The Pulitzer Prizes. 2017. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ "Jubilant Edmonia Lewis". 31 January 2017. Archived from the original on i March 2018. Retrieved 1 Baronial 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Kristin (November 2016). "Atkins, Jeannine. Stone Mirrors: The Sculpture and Silence of Edmonia Lewis". School Library Journal. 62 (11): 98. Retrieved 29 July 2020 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ^ Green, Penelope (25 July 2018). "Overlooked No More: Edmonia Lewis, Sculptor of Worldwide Acclaim". Obituaries: Overlooked. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ "In-Person Edmonia Lewis Commemorative Forever® Stamp Sale | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu . Retrieved 2022-01-21 .

- ^ "Edmonia Lewis and Her Stamp on American Art | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu . Retrieved 2022-01-21 .

- ^ a b Faithfull, Emily (1884). Three Visits to America. New York: Fowler & Wells Co., Publishers. p. 312.

- ^ "Newly Discovered Indian Combat by Edmonia Lewis acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art". Art Daily. xix November 2011. Retrieved 19 Nov 2011.

- ^ Gilbert, Lauren Miranda (22 October 2010). "SJPL: Edmonia Lewis Sculptures" (blog post). Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Bust of James Peck Thomas". Allen Memorial Art Museum (museum catalog record). Oberlin College & Conservatory. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Wolfe 1998, p. 120

- ^ "Catalog, "Exhibition of the Fine art of the American Negro," 1940". digital.chipublib.org . Retrieved 2021-04-01 .

- ^ American Negro Exposition, ed. (1940). Exhibition of the art of the American Negro (1851 to 1940). Chicago?. OCLC 27283846.

- ^ "Wildfire Test Pit". Allen Memorial Art Museum (exhibition clarification). Oberlin College & Solarium. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists. Seattle : University of Washington Printing. 2019.

- ^ Moorhead, Joanna (Oct ten, 2021). "Feted, forgotten, redeemed: how Edmonia Lewis made her mark". The Guardian . Retrieved 11 October 2021.

Bibliography [edit]

- Buick, Kirsten Pai (2010). Kid of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History's Black and Indian Discipline. Durham, NC: Knuckles University Press. ISBN978-0-8223-4266-iii . Retrieved one February 2017.

- Chadwick, Whitney (2012). Women, Art, and Guild (5th ed.). New York, NY: Thames and Hudson. ISBN9780500204054.

- "The Death of Cleopatra". Smithsonian American Fine art Museum (museum itemize record). Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Gold, Susanna Due west. (Spring 2012). "The decease of Cleopatra / the birth of freedom: Edmonia Lewis at the new world'due south fair". Biography. 35 (2): 318–324. doi:10.1353/bio.2012.0014. S2CID 162076591 – via EBSCO.

- Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe (1985). Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America: From the Collections of the National Museum of American Fine art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Establishment Printing. OCLC 11398839.

- Henderson, Harry; Henderson, Albert (2012). The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis: a narrative biography. Esquiline Loma Press. ISBN978-ane-58863-451-1.

- Katz, William L.; Franklin, Paula A. (1993). "Edmonia Lewis: Sculptor". Proudly Red and Black: Stories of African and Native Americans. New York: Maxwell Macmillan. ISBN978-0689318016 . Retrieved one February 2017.

- May, Stephen (September 1996). "The Object at Manus". Smithsonian. p. 20. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Nelson, Charmaine A. (2007). The Colour of Stone: Sculpting the Black Female Subject in Nineteenth-Century America. Minneapolis: Academy of Minnesota Press. ISBN978-0816646517 . Retrieved 1 Feb 2017.

- Peck, Patricia Cleveland (2007). "Casting the first rock". History Today. 57 (10).

- Perry, Regenia A. (1992). Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art . Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art. ISBN978-1566400732 . Retrieved one February 2017.

- Pickett, Mary (1 March 2002). "Samuel W. Lewis: Orphan leaves marker on Bozeman". Billings Gazette . Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Plowden, Martha Westward. (1994). "Edmonia Lewis-Sculptor". Famous Firsts of Black Women (2nd ed.). Gretna: Pelican Company. ISBN978-1565541979 . Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Richardson, Marilyn (2009). "Edmonia Lewis and Her Italian Circle," in Serpa Salenius, ed., Sculptors, Painters, and Italian republic: ItalianInfluence on Nineteenth-Century American Art, Il Prato Casa Editrice, Padua, Italy, pp. 99–110. Retrieved one February 2019.

- Richardson, Marilyn (2011). "Sculptor's Death Unearthed: Edmonia Lewis Died in 1907," ARTFIXdaily, nine January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Richardson, Marilyn (2011). "Three Indians in Boxing by Edmonia Lewis," Maine Antique Digest, Jan. 2011, p. 10-A. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Richardson, Marilyn (1986). "Vita: Edmonia Lewis," Harvard Magazine, March, 1986. Retrieved i February 2019.

- Richardson, Marilyn (July 1995). "Edmonia Lewis' The Death Of Cleopatra: Myth And Identity". The International Review of African American Fine art. 12 (2): 36. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Richardson, Marilyn (Summer 2008). "Edmonia Lewis at McGrawville: The early education of a nineteenth-century black women artist". Nineteenth-Century Contexts. 22 (two): 239–256. doi:10.1080/08905490008583510. S2CID 192202984.

- Rindfleisch, Jan. (2017) Roots and Offshoots: Silicon Valley's Arts Customs. pp. 61–62. Santa Clara, CA: Ginger Press. ISBN 978-0-9983084-0-1

- "Sculptor Edmonia Lewis' 'Cleopatra' revived and on view in Washington: Heritage Corner". New York Amsterdam News. Vol. 87, no. 22. 1 June 1996. p. 37. ISSN 1059-1818. ProQuest 390284855.

- Wolfe, Rinna Evelyn (1998). Edmonia Lewis: Wildfire in Marble. Parsippany, NJ: Dillon Printing. ISBN0-382-39714-two . Retrieved one February 2017.

- Forest, Naurice Frank (1993). Insuperable Obstacles: The Impact of Racism on the Artistic and Personal Development of Iv Nineteenth Century African American Artists. M.A. thesis. Cincinnati: Union Institute. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

Further reading [edit]

- Bearden, Romare (1993). A History of African-American Artists From 1792 to the Nowadays . Pantheon Books, Random House. ISBN0-394-57016-2 . Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Buick, Kirsten P. The Platonic Works of Edmonia Lewis: Invoking and Inverting Autobiography (PDF). pp. 190–207. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Farrington, Lisa Due east (2005). Creating Their Own Images: The History of African-American Women Artists. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Richardson, Marilyn (1999). "Edmonia Lewis". In National Council of Learned Societies (ed.). American National Biography. doi:x.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1701145.

- Richardson, Marilyn (10 October 2008). Edmonia Lewis and the Boston of Italy. The City and the Book Five: International Conference on Americans in Florence's 'English' Cemetery.

- Rindfleisch, Jan. (2017) with manufactures by Maribel Alvarez and Raj Jayadev, edited by Nancy Hom and Ann Sherman. Roots and Offshoots: Silicon Valley's Arts Community. Santa Clara, CA: Ginger Press. ISBN 978-0-9983084-0-i

External links [edit]

- Henderson, Albert (2005). "Edmonia Lewis". edmonialewis.com.

- "Edmonia Lewis biography". Lakewood Public Library. Archived from the original on 27 Jan 1999.

- Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Edmonia Lewis, African American and Native American Sculptor". Women's History. About.com. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

- Perry, Regenia A. (June 1976). "Selections of nineteenth-century Afro-American Art" (PDF). Exhibition Catalog. Metropolitan Museum of Art: ix. OCLC 893699642. b10403693.

- "Night (2 Sleeping Children)". Sculpture. Baltimore Museum of Art. 1870. 2003.10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2017-02-01 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmonia_Lewis

Post a Comment for "Forever Free Art by Afrian American Women Artists and Exhibit and Conference"